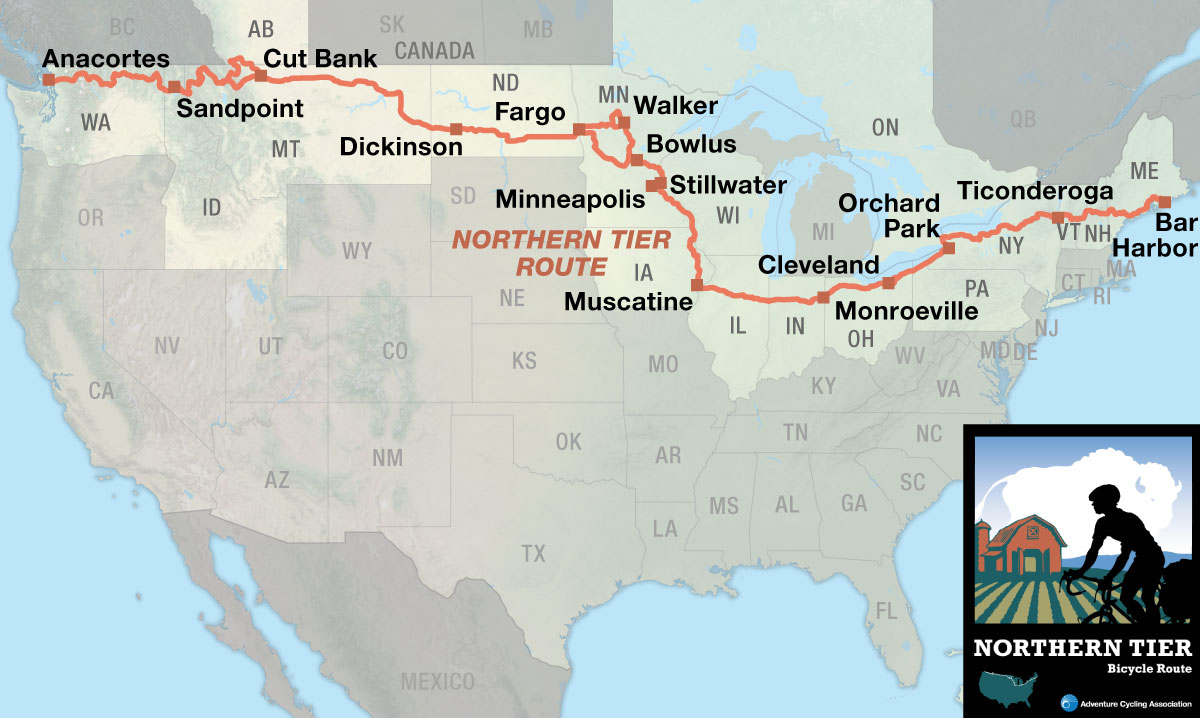

Northern Tier

Cross the nation near the U.S. and Canada border.

The western end of the Northern Tier begins at sea level and offers large expanses of mountains, the Great Plains, and some beautiful farmland areas in between. The route can be ridden from late spring to late fall. Due to snow, State Highway 20 east of North Cascades National Park in Washington is only open through certain dates. The same is true for Going-to-the-Sun Road in Glacier National Park in Montana, which is usually closed until mid June. Even in the height of summer in July, cyclists must be prepared for cold nights and occasional snow in the higher elevations during storms. Due to changing local conditions, it is difficult to predict any major wind patterns, though tornadoes can be common. They slice across the heartland each year, generally heading north and east, and mostly occur in May and June in Wisconsin, Iowa and Illinois. The Midwest and Great Lakes summers can be hot, especially inland. Along the Great Lakes, breezes provide cooling and are sometimes a friend and sometimes a foe.

The Northern Tier begins in Anacortes, Washington, which is located on a peninsula in Puget Sound. Anacortes is also the jumping-off point for folks going to the San Juan Islands, a favorite cycling destination. At the start, the combination of lush forest and ocean feeds and moistens the soul. Heading eastward along the rushing Skagit River, you carry that feeling up to the top of Rainy and Washington passes in the Cascade Mountains. Descending to the east side of the Cascades brings you into the drier part of the state and the widely known orchard country of the Okanogan Valley. Leaving this valley, you’ll be climbing and descending several more passes full of ponderosa pines and finding many sleepy farming communities along the rivers you cross. The river valleys tend to run in a north-south direction across the northwestern part of the United States, and because the route travels west to east, you will be working your way up and down. There are plenty of towns, rivers, lakes, mountains and forests in eastern Washington, Idaho, and western Montana until you reach Cut Bank, on the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains.

The spectacular Going-to-the-Sun Road in Glacier National Park is a hard climb but well worth it for the scenery. The route takes a jump into Canada to access Waterton Lakes National Park, and then you’ll head back into the States at Del Bonita, a little-used border crossing. Cut Bank is the beginning of the Great Plains, and from here on you’ll start praying for tailwinds. Supposedly, heading eastward, tailwinds predominate in the summer. Afternoon thundershowers are a constant companion out on the Plains. The plains of Montana eventually transform into the green rolling hills of western North Dakota. From Glendive, Montana, to Bismarck, North Dakota, the route follows the I-94 corridor, alternating between the interstate and parallel county roads.* Sunflowers are everywhere, and they become the crop of choice as the terrain flattens out in eastern North Dakota. Fargo is located on the banks of the Red River, on the border of North Dakota and Minnesota.

*Oil and gas development in the Bakken Oil Shale Field of western North Dakota and northeastern Montana prompted a change in routing in 2012 to avoid the area around Williston, North Dakota. Because many roads with minimal to no shoulders now have high levels of truck traffic, and are felt to be unsafe for bicyclists, the route was moved to go through southern North Dakota.

Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Iowa stand out as some of the greenest and lushest of all the states along the route. From either direction, this greenery proves to be a relief from the giant plains to the west and acres of farmland to the east. You’ll learn a lot about the history of the Mississippi River as you follow it southward.

Heading east from Fargo and Moorhead in the Red River Valley, you begin to slowly leave the Great Plains. Lakes and hills become the standard scenery, and the resident mosquitos increase in number. The birthplace of the Mississippi River is in Lake Itasca State Park, in northern Minnesota. This area is so full of forests, lakes, and rivers that it draws many recreationalists during the summer months. The route utilizes many rail-trail facilities as you ride south until it heads east around the cities of Minneapolis, St. Paul, and surrounding towns. There is a spur into Minneapolis-St. Paul that ends with access to the airport. Along the St. Croix and Mississippi rivers, the towns are older and the buildings much more historic. At Prescott, Wisconsin, the St. Croix joins the Mississippi, and the route again follows it southward for 175 miles. You’ll ride the Great River State Park Trail, an old railroad bed surfaced with finely crushed limestone through Perrot State Park and the Upper Mississippi River National Wildlife Refuge. As you enter Iowa, you may think that the terrain is going to flatten out, but the hills continue after leaving the river. Small laid-back farm towns are abundant through Iowa. Muscatine is an old industrial town located on the Mississippi River.

East of the river, the route traverses the large prairie farms of central Illinois and the smaller farms of Indiana and Ohio, eventually reaching the shore of Lake Erie at Huron, Ohio. Here a side trip can take you to nearby Cedar Point Amusement Park, which features the greatest number of the most pulse-raising roller coasters in the country. Or you can take a ferry to one or more of the Lake Erie islands and visit the area where Admiral Perry defeated the British fleet in the War of 1812. Heading through busy Cleveland, you’ll pass the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, the Science Center and its IMAX theater, a retired Great Lakes iron ore freighter, and a World War II submarine.

Along the lake shore in eastern Ohio and Pennsylvania, the route passes through small towns, where tourists flock to the shore during summer. In Erie, Pennsylvania, you can explore the miles of sand beach at Presque Isle State Park and the replica of the sailing ship Niagara, Admiral Perry’s flagship in the War of 1812 Battle of Lake Erie. Leaving Erie, the route enters the fruit and wine region of Pennsylvania and New York and hugs the relatively rural lake shore to the outskirts of Buffalo, New York. Views across Lake Erie of the Buffalo skyline and Canada usher the cyclist into the bustle of the southern end of the metropolis. In the suburbs to the Peace Bridge, ride carefully through the city streets. The route takes you to the lakefront Buffalo Naval and Military Park with World War II vessels open for visits.

After crossing the Peace Bridge into Canada you’ll follow one of the most scenic recreational trails in North America along the Niagara River to Niagara Falls. Take the cable car ride across the Whirlpool Rapids and visit the other attractions along the trail. Then you’ll cross back into the U.S., enjoying the view of the Niagara Gorge. Heading east, the route uses the Erie Canalway Trail for 86.5 miles along a waterway dripping with history. Take the time to explore the towns along the canal. At Palmyra, the route turns north to Lake Ontario, where it follows the lake shore to Sodus Bay, dips inland to Fulton, and then leaves the Great Lakes to cross the Adirondack Mountains and arrive at Ticonderoga on Lake Champlain. A visit to Fort Ticonderoga will give meaning to Revolutionary War history.

After a short ferry ride over the lake, you are in New England, cycling through Vermont farmland, forested hills, and picturesque villages. In New Hampshire, the route follows the Connecticut River, passing through the villages of Orford with its ridge houses and Haverhill, a classic New England village with its fenced village commons and old homes. The route crosses the White Mountains, the backbone of New Hampshire, on the famous Kancamagus Highway. Mt. Washington, noted for its fierce weather, is just a few miles north, and the Kancamagus shares some of its weather reputation. Be prepared, even in summer. Entering Maine, you’ll traverse forests and fields, arriving at Rockport on the coast. Allow time to savor the quintessential ambiance of the coastal towns. Before crossing the Penobscot River, stray off route to visit Ft. Knox, an exceptionally well-preserved unused Revolutionary War fort. Finally, don’t end your trip without cycling the gravel carriage paths of Acadia National Park and viewing a sunrise from atop Cadillac Mountain. The park is near the town of Bar Harbor, at the end of the route.

Photo by Chuck Haney

The route lets you warm up for about 100 miles before any prolonged climbing begins. There are four major passes in the first 300 miles, and Sherman Pass is the highest at 5,575 feet. The terrain then becomes rolling, the route following river valleys until you reach Glacier National Park. Logan Pass, on Going-to-the-Sun Road, is the last major climb in the Rocky Mountains. There’s a series of roller-coaster hills heading into Canada. Once you get about 20 miles east of the Rockies, you’re truly in Big Sky country with moderately flat countryside. The plains roll out through Montana and occasionally become hilly in western North Dakota, and then the route flattens out in eastern North Dakota and Minnesota.

In Wisconsin and Iowa the terrain is continuously rolling. Ask any Iowan if Iowa is flat, they will respond with a “No,” especially in the northeastern part of the state.

From the Mississippi River at Muscatine, Iowa to Palmyra, New York, the route is virtually flat. Illinois has some gently rolling prairie and is treeless except in towns. The trees increase in Indiana. East of Cleveland, Ohio, the route climbs to a low ridge for a few miles and then descends back to the lake shore until Buffalo, New York. From Buffalo to Palmyra, the route experiences only slight elevation changes at the locks along the Erie Canal. The mountains in New York, Vermont, and New Hampshire extend north and south, and the route travels east-west so the remainder of the route has a lot a variety — flat sections along river valleys and several challenging climbs. The Kancamagus Pass at 2,855 feet is the highest point on the eastern end of the Northern Tier Route.

| Northern Tier - Main Route | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Section | Distance | Elevation | Total Climb | Avg. Climb/mile |

| Total | 4296.3 miles | Minimum: 0 ft.Maximum:6,650 ft. | 174,315 ft. east bound174,020 ft. west bound | 41 ft. per mi. east bound41 ft. per mi. west bound |

| 1 | 454.9 miles | Minimum: 0 ft.Maximum:5,510 ft. | 28,185 ft. east bound26,170 ft. west bound | 62 ft. per mi. east bound58 ft. per mi. west bound |

| 2 | 444.9 miles | Minimum: 1,945 ft.Maximum:6,650 ft. | 26,565 ft. east bound25,080 ft. west bound | 60 ft. per mi. east bound56 ft. per mi. west bound |

| 3 | 567.3 miles | Minimum: 2,045 ft.Maximum:4,725 ft. | 24,560 ft. east bound25,860 ft. west bound | 43 ft. per mi. east bound46 ft. per mi. west bound |

| 4 | 342.6 miles | Minimum: 885 ft.Maximum:2,570 ft. | 3,635 ft. east bound10,135 ft. west bound | 11 ft. per mi. east bound30 ft. per mi. west bound |

| 5 | 174.8 miles | Minimum: 875 ft.Maximum:1,605 ft. | 3,960 ft. east bound3,585 ft. west bound | 33 ft. per mi. east bound21 ft. per mi. west bound |

| 6 | 256.0 miles | Minimum: 675 ft.Maximum:1430 ft. | 5,415 ft. east bound6,175 ft. west bound | 21 ft. per mi. east bound24 ft. per mi. west bound |

| 7 | 372.7 miles | Minimum: 550 ft.Maximum:1215 ft. | 14,905 ft. east bound14,875 ft. west bound | 40 ft. per mi. east bound40 ft. per mi. west bound |

| 8 | 405.7 miles | Minimum: 440 ft.Maximum:870 ft. | 7,085 ft. east bound6,855 ft. west bound | 17 ft. per mi. east bound17 ft. per mi. west bound |

| 9 | 411.3 miles | Minimum: 570 ft.Maximum:940 ft. | 7,345 ft. east bound7355 ft. west bound | 18 ft. per mi. east bound18 ft. per mi. west bound |

| 10 | 426.5 miles | Minimum: 240 ft.Maximum:2200 ft. | 19,230 ft. east bound19865 ft. west bound | 45 ft. per mi. east bound47 ft. per mi. west bound |

| 11 | 439.6 miles | Minimum: 0 ft.Maximum:2855 ft. | 28,430 ft. east bound28,065 ft. west bound | 65 ft. per mi. east bound64 ft. per mi. west bound |

| Northern Tier Alternates | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Section | Distance | Total Climb | Avg. Climb/mile |

| Curlew Alternate | 1 | 102.5 miles | 9,155 ft. east bound8740 ft. west bound | 89 ft. per mi. east bound85 ft. per mi. west bound |

| West Side Alternate | 2 | 45.9 miles | 5,275 ft. east bound4,930 ft. west bound | 115 ft. per mi. east bound107 ft. per mi. west bound |

| West Side Alternate | 2 | 45.9 miles | 5,275 ft. east bound4,930 ft. west bound | 115 ft. per mi. east bound107 ft. per mi. west bound |

| Marias Alternate | 2 | 102.9 miles | 5,000 ft. east bound4415 ft. west bound | 49 ft. per mi. east bound43 ft. per mi. west bound |

| SR 200 Alternate | 2 | 11.5 miles | 750 ft. east bound590 ft. west bound | 65 ft. per mi. east bound51 ft. per mi. west bound |

| Trails Alternate | 5 | 168.2 miles | 2,680 ft. east bound2390 ft. west bound | 16 ft. per mi. east bound14 ft. per mi. west bound |

| Heartland Alternate | 5 | 39.3 miles | 665 ft. east bound800 ft. west bound | 17 ft. per mi. east bound20 ft. per mi. west bound |

| Paul Bunyan Connector | 6 | 9 miles | 555 ft. east bound575 ft. west bound | 62 ft. per mi. east bound64 ft. per mi. west bound |

| Minneapolis/St. Paul Spur | 6 | 35.5 miles | 1,150 ft. east bound995 ft. west bound | 32 ft. per mi. east bound28 ft. per mi. west bound |

| Heights Alternate | 9 | 38.6 miles | 1,570 ft. east bound1,570 ft. west bound | 41 ft. per mi. east bound41 ft. per mi. west bound |

| Flats Alternate | 9 | 1.1 miles | 80 ft. east bound80 ft. west bound | 73 ft. per mi. east bound73 ft. per mi. west bound |

Services are generally good along this route. There is a 73-mile stretch of limited services between Cardston, Alberta, and Cut Bank, Montana. There are also some sporadic spots lacking services in central Montana, but nothing is farther apart than a day’s ride. The people of the towns across the plains of Montana and North Dakota are super generous and genuine. Camping in town parks is not uncommon. Only a few bike shops exist between Whitefish, Montana, and Bismarck, North Dakota. In the midwest, townsfolk are friendly. Campgrounds are reasonably plentiful, but there are a few gaps, and advanced planning is needed if you are camping.

Some campgrounds will charge a cyclist traveling alone less if they have hiker/biker sites, but often they will charge the price of a regular tent or RV site, and that can easily be $10-$40/night (higher in the east). The maps list churches that have opened their doors to cyclists, but they aren’t all that closely spaced. If you’re friendly and ask around, you can often get yourself invited to camp in a yard. Our routes sometimes go through national forests (moreso in the west) and you are allowed to camp anywhere on national forest land as long as you “pack it in, pack it out.” Many city parks are free to camp in.

You may also wish to sign up with Warmshowers, a reciprocal hospitality site for bicycle travelers, for other overnight options.

This route is best ridden in late spring to mid-fall (typically May to September). Due to heavy snow falls, State Route 20/North Cascades Highway in North Cascades National Park is usually closed mid-November to mid-April though the park remains open with limited access. For an opening date call the Park at (360) 856-5700. Going-to-the-Sun Road in Glacier National Park is usually closed until early to mid June and has limited hours for cyclists which is noted on the map. Call the Park for an opening date at (406) 888-7800. Some cyclists may want to do the eastern portion of this route during the colors of autumn. If you do, call ahead to verify campgrounds because many close after Labor Day. If staying indoors, make advance reservations.

Route Highlights

Northern Tier Highlights

- North Cascades National Park, Section 1

- Ross Lake National Recreation Area, Section 1

- Glacier National Park, Section 2

- Going-to-the-Sun Road, Section 2

- Waterton Lakes National Park, Section 2

- Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail Interpretive Center, Great Falls, Montana, Section 3

- Theodore Roosevelt National Park, Section 3

- Maah Daah Hey Trail, Section 3

- Long Lake National Wildlife Refuge, Section 4

- Sheyenne National Grassland, Section 4

- Itasca State Park, Section 5

- Heartland Alternate, Section 5

- Minneapolis/St. Paul Spur, Section 6

- Upper Mississippi River National Wildlife Refuge, Section 7

- Effigy Mounds National Monument, Section 7

- Field of Dreams, Section 7

- Central Lowlands, Section 8

- Cedar Point Amusement Park, Section 9

- Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Cleveland, Ohio, Section 9

- Peace Bridge, Section 10

- Niagara Falls, Section 10

- Adirondack Park, Section 10

- White Mountain National Forest, Section 11

- Acadia National Park, Section 11

More Route Resources

- U.S. Bicycle Route System

- How to Travel with your Bike on Amtrak

- U.S. Bicycle Route 10 (Washington)

- No-Turn-Away Bike Camping Policies (Minnesota, Washington)

- Washington State Ferry System

- North Cascades Highway (State Route 20) status (Washington)

- Tommy Thompson Trail (Washington)

- Cascade Trail (Washington)

- U.S. Bicycle Route 10 (Idaho)

- Idaho State Bike Maps (Idaho)

- Serenity Lee/Long Bridge Trail (Idaho)

- Bicycling in Glacier National Park (Montana)

- Going-to-the-Sun Road Information and Transit System (Montana)

- U.S. Chief Mountain border crossing

- Canadian Chief Mountain border crossing

- U.S. Bicycle Route 45 (Minnesota)

- Paul Bunyan Trail (Minnesota)

- Heartland State Trail (Minnesota)

- Central Lakes Trail (Minnesota)

- Lake Wobegon Trail (Minnesota)

- Soo Line Trail (Minnesota)

- Sunrise Prairie Trail (Minnesota)

- Hardwood Creek Trail (Minnesota)

- Minneapolis and St. Paul Twin Cities bike map (Minnesota)

- Access to Minneapolis/St. Paul International Airport

- Wisconsin DOT bike maps

- Great River State Park Trail (Wisconsin)

- Heritage Trail (Iowa)

- U.S. Bicycle Route 35 & 35A (Indiana)

- Cyclists Only Lodging in Monroeville (Indiana)

- Cleveland Lakefront Byway (Ohio)

- U.S./Canada Visa Information

- Niagara Recreation Trail (Ontario)

- Information on bypassing Canadian routing on Section 10 from New York DOT

- Erie Canalway Trail (New York)

- U.S. Bicycle Route 1 & 1A (Maine)

- Connect and share photos with other riders on Instagram: #acaNoTier

Updates to Recently Released Maps

If you are planning a bike tour, be sure to get the most recent map updates and corrections for your route by selecting the route, and the appropriate section(s), from the drop-down menu below.

Over time maps become less useful because things change. Every year Adventure Cycling’s Routes and Mapping Department create map updates and corrections for every map in the Adventure Cycling Route Network, which now totals 52,047 miles. With the help of touring cyclists like you, we receive updates on routing, services, camping, and contact information. Until we can reprint the map with the new information, we verify the suggested changes and publish corrections and updates here on our website.

PLEASE NOTE: Covid has been particularly hard on the small businesses along our routes. While we do our best to keep the maps and these online updates current, you may encounter more closed businesses and longer stretches with limited or no services.

Refer to these updates for the most current information we have and submit reports of changes to the Route Feedback Form for the cyclists coming after you.

NOTE: Map updates and corrections only pertain to long term changes and updates. For short term road closures, please see the Adventure Cycling’s Routes Temporary Road Closures discussion in our Forums.